Ashley Riley, 28, wondered whether she would survive.

The new man in her life, the one she thought had potential, had become her kidnapper, she said.

His arrest following a bizarre night of terror made her feel no safer.

In fact, the way Bedford Municipal Court handled her case left her wondering if she would “have to be killed” to be taken seriously.

A man in uniform

Riley met 31-year-old Wilson in the lobby of her apartment building a few weeks earlier.

He was hired to work as a security guard at the Bedford Heights complex.

“I definitely trusted him,” she said. “Why wouldn’t I trust him? He’s law enforcement.”

They went on a handful of dates over the next few weeks. She said the relationship was going well.

Like her, Wilson said he was a deeply religious and a devoted family man.

It appealed to the single mom of two little girls.

“I thought he was really, really nice,” she said.

Night of terror

Riley soon realized Wilson wasn’t who she thought he was.

On the evening of May 5, they were talking inside his truck.

Out of nowhere, Wilson accused her of seeing other people.

“Next thing I know, ‘Boom!’ He hits me in my lip,” she said.

Stunned, Riley went to leave, but as she opened his passenger side door, Wilson pulled out a gun.

“He points his gun at me, he tells me, 'You're not going anywhere’,” she said.

Her bizarre night of terror had just begun.

‘I hoped that you had died’

As he held her at gunpoint, Wilson began to drive.

His first stop was an apartment complex in Warrensville Heights.

Riley recognized the buildings. It was where Wilson lived with his mother.

She said Wilson pulled up behind a dumpster and put his truck into park.

There, he struck Ashley again.

“I actually passed out for a second and when I came to, he was like, ‘Oh, you're not dead. I hoped that you had died,'" she said.

Riley struggled to breathe after the unexpected blow to her chest.

She begged Wilson for water.

To her surprise, Wilson obliged. She said he drove to a nearby convenience store and went inside.

Riley seized the moment.

A missed opportunity

Fearing Wilson would shoot her — or someone else — if police showed up, Riley decided against calling 911.

Instead, she worked to create evidence.

“At that moment, I began texting my friend,” she said. “I said, ‘If something happens to me, this is who did it’."

Soon, Riley heard someone calling her name.

In spite of the danger, her friend had come looking for her.

She contemplated running to safety, but just as she was about to escape, she looked toward the store’s window. She saw Wilson staring at her from inside.

She stayed put.

“It was like something out of a movie,” she said. “It's like being so close to help, yet so far away."

Home free?

Wilson’s next decision left Riley shocked again.

He drove her home.

His gun at his hip, he forced his way inside her apartment and sat on her couch.

Wide awake with fear, she spent the night sitting nearby, scared to say or do anything.

After all, her daughters, ages 5 and 10, were just feet away, fast asleep in their bedroom.

“I honestly didn't know if I would make it out of that night, away from him, alive . . . to my girls,” said Riley.

Come morning, Wilson had another surprise in store.

He got up and left her apartment.

Riley finally felt safe enough to dial 911, but before officers arrived, Wilson returned.

From her building’s lobby, he called her, begging her to let him inside her apartment.

Wilson told her he only wanted “a hug.” He promised to turn himself in.

Knowing police were on the way, Riley stalled him on the phone.

Minutes later, they arrived and Wilson was arrested.

Relief washed over Riley. She thought her ordeal was over.

She was wrong.

Out on bond

For Riley, what happened next was as bizarre as her night of terror.

Less than 24 hours after his arrest, Wilson was free.

Bedford Municipal Court released him on a personal bond after charging him with only misdemeanors, menacing by stalking and a weapons violation.

By the following day, Bedford Heights police had provided the court with additional information about Riley’s terror-filled hours.

Prosecutors added kidnapping, a first-degree felony, to Wilson’s charges. It didn’t make a difference.

At his arraignment, Judge Brian J. Melling set Wilson’s bond at $10,000. Wilson paid ten percent.

He remained free.

Riley couldn’t believe it, especially since this wasn’t Wilson’s first brush with the law.

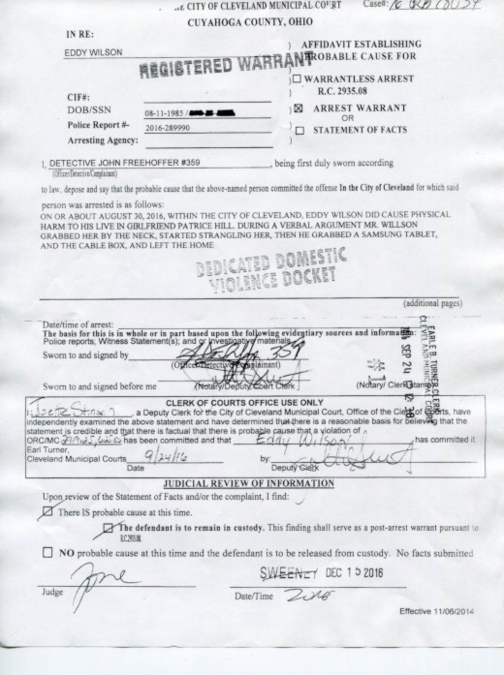

Wilson was already facing charges in Cleveland.

In 2016, he was charged with domestic violence after a woman accused Wilson of strangling her.

He eventually pleaded guilty to disorderly conduct.

God and a glock

Anthony Mattox was also frightened by Wilson’s release.

“Instantly, we knew we had a major security issue,” he said.

Mattox is the senior pastor at Empowerment Church in East Cleveland where Riley works and attends services.

Just hours before his arrest, Wilson wrote Mattox a message on Facebook, requesting the pastor arrange a meeting between him and Riley.

Mattox was alarmed, especially since he and Wilson have never met.

“We don't know his mindset, we don't how stable he is, we don't know if he's going to pop up at the church and try to hurt Ashley," said Mattox.

Unwilling to take chances, Mattox began packing his pistol 24/7.

“I always make a joke to my congregation that I trust in both God and Glock,” he said. “I believe we need them both here to make sure we’re protected.”

The judge's ruling

“Bond is not punitive,” said Judge Brian J. Melling.

Melling is the presiding judge for Bedford Municipal Court.

He set Wilson’s bond at $10,000.

“Bond is basically to insure the defendant’s appearance in court,” he said. “That’s, in a nutshell, what bond is.”

At first, Melling said the court made a mistake when it released Wilson on personal bond before his formal arraignment in court.

“We see dozens of these cases,” he said. “We’re never going to be 100 percent perfect and that’s one that was potentially less than 100 percent perfect.”

Later on in the interview, Melling reversed his position.

“The fact of the matter is whatever judgment was made initially was correct because, in fact, he (Wilson) did appear . . . so I don’t believe there was a mistake made there, this was a situation where, over the weekend , you don’t have all the facts and we didn’t get a lot more facts until Monday,” he said.

Broken system

The American idea of bail can be traced back to medieval England, according to the PreTrial Justice Institute, a non-profit organization dedicated to making bail more fair and effective.

Melling was correct.

Bail’s primary purpose is to ensure defendants return to court.

Judges are also encouraged to consider whether defendants pose a significant risk to public safety.

However, defendants who end up behind bars are usually there because they are too poor to pay the fee.

According to a report by the Ohio Sentencing Commission, defendants with money buy their freedom, regardless of the charges against them, while poor defendants, unable to afford bail, languish behind bars awaiting their trials.

As a result, courts around the country, including many in Ohio, are looking at ways to decrease the number of non-violent offenders behind bars and while keeping dangerous offenders kept off the streets.

“It functions well, but there are places where it can be improved, said Judge Ken Spanagel of the Parma Municipal Court. He's also a member of the Ohio Sentencing Commission.

The solution?

While it’s not considered a panacea, a new method of assessing bail that reduces bias and subjectivity within the system has emerged.

Pretrial risk assessment tools use data collected from closed cases to assess how likely a defendant is to flee or commit another crime while out on bond.

The tools are typically a questionnaire or form that categorizes defendants’ risk of missing court appearances or engaging in new criminal activity.

Besides Ohio, the sentencing commission report found courts in at least 13 other states have adopted pretrial assessment tools.

In Ohio, On Your Side Investigators found Cuyahoga, Lucas, Stark, and Summit counties now use pretrial assessment tools.

Cuyahoga County has not studied the effects of their tool, according to Darren Toms, Cuyahoga County Court of Common Pleas spokesman.

Cleveland Municipal Court plans to adopt a pretrial assessment tool in August.

“A better objective opinion”

After struggling with jail overcrowding, courts in Lucas County adopted a pretrial assessment tool created by the Arnold Foundation, a non-profit foundation, in 2015.

The foundation’s tool uses nine factors to determine the likelihood defendants will return to court or engage in new criminal activity if they are released from jail.

“A risk tool is giving a better objective opinion on somebody,” said Michelle Butts, Deputy Director, Regional Court Services, Lucas County Court of Common Pleas.

It’s still ultimately up to the judge to set bond.

After using the tool for one year, court administrators reviewed the results.

“I was astounded,” said Butts.

During 2016, they discovered there was a 50 percent decrease in new criminal activity by defendants released on bond.

There was also 30 percent decrease in defendants’ failure to appear in court.

“We know we are holding the right people now,” she said.

Cuyahoga’s courts

In spite of the Toledo-area court’s success, On Your Side Investigators found Cleveland Municipal Court is the only one of Cuyahoga County’s 13 municipal courts with immediate plans to adopt a pretrial assessment tool, including Bedford Municipal Court, which released Eddie Wilson.

Several municipal court judges, including Spanagel, said they already consider the factors used by pretrial assessment tools, like a defendant’s criminal history, when they set bond.

“The tool is what I’m already using,” said Spanagel. “I’m just not calling it ‘The Tool.'”

Other judges said their courts don’t have the resources to implement pretrial assessment tools, noting county courts have staff dedicated to bail assessments for defendants’ arraignments. Municipal court judges said they set bond by relying on police officers’ recommendations, court records and their own experience.

Back behind bars

Riley hopes they reconsider.

“I should be able to sleep at night,” she said.

On June 20, Wilson once again destroyed her sense of safety.

She said he tried to call her using Facetime, a violation of his temporary protection order.

She screen grabbed the call. Then, she phoned prosecutors.

This time, she received better results.

Due to the seriousness of the charges against him, Wilson’s case had been transferred to the Cuyahoga County Court of Common Pleas.

During a June 28 hearing, as our cameras were rolling, Judge Shannon Gallagher, said Wilson’s original bond was “set too low.”

Gallagher raised it to $50,000 and ordered Wilson to wear a GPS monitor.

Riley feels safer now, but her night of terror still haunts her.

“I’ve never had a gun pointed at me before,” she said. “I’ve never been held against my will like that before. It was one of the most terrifying situations I’ve ever been in my life."