CLEVELAND — Cleveland City Council isn’t rushing to approve a proposed exit deal with the Browns – an agreement to end a legal battle and speed up lakefront development Downtown.

On Monday, council members spent three hours dissecting the deal during a joint committee hearing that ended without a vote. Some members pushed back, saying they believe Cleveland can strike a better bargain with team owner Haslam Sports Group. Others seemed resigned, acknowledging that something is better than nothing.

Mayor Justin Bibb’s administration still hopes to win council’s support for the deal by the end of this year. The agreement calls for the city and the Browns to end a court fight over the team’s planned move to Brook Park.

RELATED: Browns, Cleveland reach $100M settlement, paving the way for Brook Park stadium move

Cleveland ultimately would receive $50 million for the lakefront and $20 million for “community benefits projects.” And Haslam Sports Group would pay to tear down the existing, city-owned stadium and prepare the land beneath it for redevelopment.

In exchange, the Browns would get a smoother road to Brook Park – and the option to extend their existing lease Downtown by up to two years, until early 2031, if their enclosed, suburban home isn’t ready on time. The team still aims to start playing in Brook Park in 2029.

RELATED: Proposed settlement gives Browns the option to stay put at Cleveland stadium for two more years

“There’s a hard stop after two years,” Cleveland Law Director Mark Griffin said of the lease extension provision, which some council members criticized. “We want certainty on the lakefront. We want to know that we can move forward.”

The Bibb administration and Haslam Sports Group are still fleshing out the deal, based on a term sheet they signed last month.

It’s unclear when City Council will see the full agreement. The city and the Browns have pressed pause on their lawsuits while working to formalize their truce.

'These are our Browns'

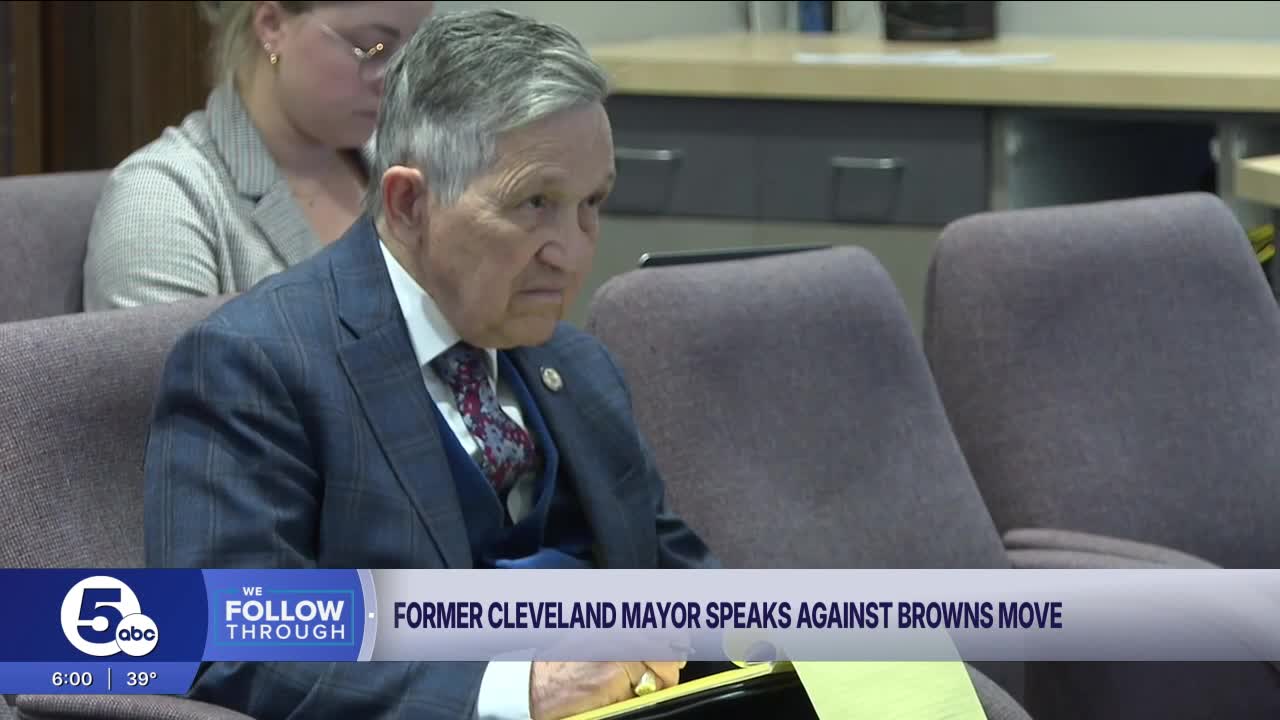

Meanwhile, the city’s lawyers are asking a Cuyahoga County judge to toss a lawsuit filed by Dennis Kucinich, a former Cleveland mayor who’s trying to keep the stadium battle going. On Monday, Kucinich sat through the entire council committee hearing, waiting for a chance to speak at the end.

“Right now, we have something that cities all over America wish they had – an NFL franchise,” he said. “We have it. … These are our Browns. We should not let them move.”

But top Bibb administration officials say they could only delay or complicate a move – not stop one entirely. The city’s spent more than $1 million on legal bills so far. And there’s no guarantee of a win in court, where Cleveland and the Browns were sparring over a state law designed to make it harder for pro sports teams to leave publicly subsidized facilities.

Kucinich was the original author of that law, commonly called the Modell law after Art Modell, the former Browns owner who moved the team to Baltimore in the 1990s.

The law, which gives communities and local investors a shot at buying a team that’s threatening to move, has never been fully tested in court.

RELATED: The Modell law was used before; what a Columbus battle tells us about the Browns

And Ohio lawmakers changed it this year, so the law now only applies to teams that are looking to leave the Buckeye State.

RELATED: State lawmakers change the Modell law

Kucinich believes City Hall is selling out – at too low a price.

“Don’t do it,” he urged council members. “Look further. Take your time. Get experts to review all the costs and values involved.”

Councilmen Mike Polensek and Brian Kazy said they plan to vote against the deal.

“I’d go down fighting bloody and lose before I would give up,” Kazy said.

Council members asked about the money for community benefits projects, which could include upgrades to city buildings, new construction, educational programming and recreation programs. City council and the administration would jointly choose the projects and submit a list to Haslam Sports Group each year.

Councilman Anthony Hairston acknowledged that he and his colleagues have tough and potentially unpopular decisions to make – and they need to accept reality.

“Do I think that we can take a good deal and make it a great deal? I think there’s some opportunity there,” Hairston said of the settlement proposal. “However, I give kudos to the administration for the work that you have put in to get us to the point. Because it’s very real that we could be left with zero. Zero.”

'Stadiums are built very specifically'

In response to questions from council members, the Bibb administration provided more details about the city’s spending obligations for the existing stadium – and potential savings after the Browns leave.

Cleveland is still on the hook for roughly $46 million in spending at Huntington Bank Field, between debt payments and repair bills. That money falls into three main buckets:

- The city owes a little less than $27.9 million in principal and interest on debt issued to pay for stadium construction in the 1990s. Those payments will be done in 2028.

- Cleveland owes the Browns $6 million for stadium repair bills that the team picked up in 2014 and 2015. The city is scheduled to repay the money, without interest, in $2 million installments in 2026, 2027 and 2028.

- And as the team’s landlord, the city is obligated to pay for future capital repairs at the stadium. That typically costs approximately $4 million a year. Cleveland expects to pay roughly $12 million over the next three years for repairs. City officials say those repairs will be limited to the basics – spending that’s essential for the health and safety of people working at or visiting the stadium.

Griffin, the law director, said the proposed settlement requires the Browns to start tearing down the stadium within six months of playing their last game there. Demolition will take 18 months. Officials said the stadium can’t easily be reused for another purpose.

“Stadiums are built very specifically now to a sport that it’s catering to. So a stadium that might be a good stadium for a football team would not necessarily be a good stadium that’s for a soccer team,” said Bonnie Teeuwen, the city’s chief operating officer.

'Unlock the power of that lakefront'

The North Coast Waterfront Development Corporation, a nonprofit launched by the city to realize the city’s lakefront plans, is reviewing proposals from developers for 50 acres of the Downtown lakefront, including the stadium site.

RELATED: Cleveland seeks developers for 50-acre lakefront site, including Browns stadium

Scott Skinner, the organization’s executive director, said an announcement about developer selections is coming soon. He expects to have an updated lakefront plan to show to council and the community in mid-2026.

“We are reimagining now what that plan looks like without a stadium,” he said during Monday's committee hearing.

Sports and other recreational uses are part of the conversation. So are apartments, hotels and entertainment.

There’s no way to replicate the draw of an NFL stadium, bringing 65,000 people to the lakefront 10 days a year, he said. But it’s possible to build something that will attract smaller crowds, but much steadier traffic, throughout the year.

Some council members questioned the focus on lakefront development in a cash-strapped city with so many urgent needs. But officials said it’s long past time to make more of Cleveland’s waterfront – and that a reimagined lakefront will help the city overall.

“There are cities that would cut their proverbial fingers off to have the natural assets that we have out there,” said Tom McNair, the city’s integrated development chief.

“When we unlock the power of that lakefront,” he added, “it’s going to lead to a hell of a lot more investment in Downtown Cleveland.”